Chapter 2: Hierarchy

Ray Sutton

Narrated By: Devan Lindsey

Book: That You May Prosper

Topics: Doctrinal Studies

Library: Gary North Library

Subscribe to the Audiobook

iTunes Spotify RSS FeedChapter Text

A. First Point of Covenantalism

(Deuteronomy 1:6-49)

There was a time when God’s people were very different from the rest of the world. Everybody else had a king, but they did not.

God’s children did not like being “politically alienated.” They complained. God heard them. He had planned for a king (Christ), but they wanted a king like the rest of the world’s leaders. He gave them what they wanted, choosing the best looking, tallest, strongest young man He could find, Saul.

Saul started off well, but it was not long before he displeased God. Saul’s basic problem was he could not follow orders, the fundamental requirement to be a soldier in God’s army. God’s prophet, Samuel, would tell him to do one thing, and he would do another.

One day, God sent Samuel to tell Saul to destroy the Amalekites. The specific instructions were,

Go and strike Amalek and utterly destroy all that he has, and do not spare him; but put to death both man and woman, child and infant, ox and sheep, camel and donkey (I Sam. 15:3).

Saul’s orders were clear. With God on his side, he could not lose. The victory was swift. But Saul decided to take a short-cut to submission. He kept some of the sheep and other spoils of war, as well as the king, Agag. Samuel was extremely upset because he knew God would be angry with the whole nation for this insubordination.

When Samuel found Saul, the disobedient king tried to justify his behavior, saying he was going to use the sheep and spoils of war to offer sacrifice to God. He was even willing to use sacrifice as an excuse for not submitting to God’s commandments.

Samuel said,

Has the Lord as much delight in burnt offerings and sacrifices

As in obeying the voice of the Lord?

Behold, to obey is better than sacrifice,

And to heed than the fat of rams.

For rebellion is as the sin of divination,

And insubordination is as iniquity and idolatry.

(I Sam. 15:22-23)

Saul had violated the Lord’s hierarchy. Even though he was king, he was supposed to submit to the prophet Samuel. Why? The prophet was the embodiment of the Word of God, a hierarchy mediating life and death. To disobey the prophet was to disobey the covenantal system of authority.

Samuel’s words – “Rebellion is as the sin of witchcraft” (divination) – summarize the relationship between authority and idolatry. Rebellion is a rejection of some sort of representative authority of God, who by definition represents God. It substitutes another hierarchy, in Saul’s case, a medium. He started off rebelling against the authority structure God had placed over him, and ended up in witchcraft. Perhaps Saul thought that he, a covenantal man, would never stoop to such a thing. Eventually, however, he did exactly as Samuel had predicted; he began to consult a witch (I Sam. 28:3-7). He went to a foreign authority to have life mediated to him. At this point, he committed idolatry, since the medium represented another lord, Satan himself.

Idolatry and rebellion bring us to the logical connection between the first and second points of covenantalism. Saul’s behavior links the two. Reject the truly transcendent God, attempt to find transcendence and immanence in the words of a medium, and the result is rebellion. How? If God is transcendent, the true Covenantal Suzerain, then He establishes His authority on earth. He makes His Lordship visible by establishing representatives, a hierarchy. He establishes delegated authorities, who work from the bottom up, not a bureaucracy, working from the top down. Saul wanted a manipulative bureaucracy in the form of mediums, instead of responsible obedience to the Word of God. When the king rejected the prophet’s mediation, he was rejecting God’s transcendent hierarchy and opting for a humanistic bureaucracy. Let us consider the second point of covenantalism to see how the Biblical hierarchy works.

The second section of Deuteronomy begins with a brief statement of the hierarchy among God’s people. Moses says,

How can I bear the load and burden of you and your strife? Choose wise and discerning and experienced men from your tribes, and I will appoint them as your heads. And you answered me and said, “The thing which you have said to do is good.” So I took the heads of your tribes, wise and experienced men, and appointed them heads over you, leaders of thousands, and of hundreds, of fifties and of tens, and officers for your tribes. Then I charged your judges at that time, saying, “Hear the cases between your fellow countrymen, and judge righteously between a man and his fellow countryman, or the alien who is with him. You shall not show partiality in judgment; you shall hear the small and the great alike. You shall not fear man, for the judgment is God’s. And the case that is too hard for you, you shall bring to me, and I will hear it” (Deut. 1:12-17).

It is really very simple. Biblical hierarchy is a series of courts with delegated authorities over each level. The procedure is from the bottom up. Since the Biblical system of authority is placed immediately after the transcendence section, it is the way in which God makes His transcendence known on earth. In the ancient suzerain covenants, a hierarchical and historical section (historical prologue) would always follow the preamble, what I have called the transcendence segment. The suzerain identified himself as Lord and then he proved it by setting up his authority in history.[1] To be precise, he made the newly conquered vassal a visible authority, one who represented him. This idea of “visible sovereignty” was copied from the archetype of all sovereignty, God.

The Biblical covenant has the same pattern. This progression of thought in Deuteronomy is very important. There is a movement from the declaration of transcendence to the temporal demonstration of transcendence, from the verbal to the visual, and from heaven to earth. This progression is the same all through the Bible. It is God’s way.

In the beginning, God created the world by His Word. What He declared was visualized. If God had declared light, and the light had not come into existence, then we could safely say that God could not declare light. The idea is that what God says comes to pass, and if it doesn’t, then God is revealed as a liar.

Enter Satan. Six days after creation, Satan tried to make God a liar. His strategy was ingenious. He struck at God’s hierarchy by taking the delegated authority given to Adam, and by actually convincing the first man to give it to him. He offered Adam divine authority in place of a delegated authority. He told man he would become like God, “knowing [determining] good and evil” (Gen. 3:5), if he ate the tree of the knowledge of good and evil. Yet, he was trying to convince Adam of something that was already true. Man was created in the “image” of God (Gen. 1:26). In this sense, he already was like God, a theomorphe. But the way to manifest God was not by “knowing” (determining) good and evil; rather, it was by ruling as a delegated authority. In the greatest deception of history, Satan had succeeded in robbing man of what he possessed by offering him what he could never have. By so doing, he effectively made the first man obey his authority, which in turn made him the vice regent[2] of the earth, and placed diabolical leaders in office. Adam’s disobedience gave away God’s visible sovereignty, as well as his own delegated authority, and made Satan, not man, appear to be God.

The implication was devastating. Remember the progression of the manifestation of sovereignty from verbal to visual and from declaration to temporal demonstration (history)? God speaks, and man obeys. God’s authority is over man, and man’s authority is over the creation. Man mediates between God and the creation. But Satan comes, disguised as a creature which was below man, and he also speaks. Whose voice is the true voice of authority? Man is tempted to respond to the creature and disobey the Creator. Man is still an intermediary. He mediates between the Creator and the creation. This is his inescapable role. It is never a question of mediation or no mediation; it is always a question of who is sovereign above man, and who is subordinate beneath him. Satan sought ethical authority (law-giver status) over man in order to manipulate God and God’s plan for the ages. God had declared Adam as His image, yet man symbolically placed himself beneath the creation (a serpent) and over God. This was an act of rebellion. It was an attempt to reverse the order of creation by turning upside down God’s hierarchy. God had specifically told Adam that man’s rule over animals images God’s rule over creation (Gen. 1:28). Now Adam listened to Satan as the supposed sovereign law-giver. He placed himself under a creature (a serpent), and a rebellious creature at that. Satan had reversed everything – covenantally, not metaphysically.

The rest of the Bible tells the story of how God re-established not His sovereignty – He never lost it because it can’t be lost – but Adam’s hierarchical rule over the world. God did this by sending a seed who represented Him better than Adam, Seth. But one by one each seed person fell, just like Adam, until the true Son, Jesus Christ. He was the only one who could truly manifest God’s visible sovereignty. He died, rose again, and put a new delegated hierarchy on the earth again, the Church. The Apostle Paul describes this fact:

He [God the Father] raised Him [Christ, God the Son] from the dead, and seated Him at His right hand in the heavenly places, far above all rule and authority and power and dominion, and every name that is named, not only in this age, but also in the one to come. And He put all things in subjection under His feet, and gave Him as head over all things to the church, which is His body, the fulness of Him who fills all in all (Eph. 1:20-23).

Notice the progression from transcendence to hierarchy in this passage. Christ is raised and seated in heaven, and then His authority is planted on earth. The Lord declares Christ’s transcendence, and then establishes Christ’s visible sovereignty through the rule of His people as His authority.

There is no escape from the principle of man’s God-given mediatory authority. If God’s authorities do not rule, neither does He, in the sense of a public manifestation of authority. He manifests visible sovereignty through the visible authority of those who are in visible covenant to Him. The Christian always affirms that God rules over His creation. God (theos) rules (kratos). We live in a theocracy. The entire universe is a theocracy. Every human institution is a theocracy – Church, State, Family, business, etc. There is no escape from theocracy. But Christians in every aspect of their daily lives are supposed to make manifest His rule in every institution (and not just the State).[3] This is why God is interested in having earthly authority. This is why Paul encourages the Ephesian Church to take rule! Christ has conquered the powers and now He wants them out of office. It is time for Christians to take their place of authority! How is this done? First, we have to understand the central principle of hierarchy. Second, we can then analyze how God puts His people into positions of authority through accountability.

The Representative Principle

The second section of the covenant presents Israel as the Lord’s representative on the earth. They were a priesthood, a hierarchy. They not only had an internal system of representation, they represented the rest of the nations. In the Old Testament, the priests of Israel during the feast of booths (trumpets) offered sacrifices for a week in the name of the gentile nations. This feast symbolized the ingathering of the nations. On day one, they offered 13 bulls, day two they offered 12, and so on, for seven days. On the seventh day, they offered seven bulls (Nu. 29:13-34). This totalled 70 bulls, corresponding to the 70 nations that represented all the nations of the earth (Gen. 10).[4]

The Church in New Testament times serves a similar function. The New Testament compares the Church’s liturgy to the Old Testament’s: “. . . golden bowls full of incense, which are the prayers of the saints” (Rev. 5:8; cf. 8:3). The same function of prayer was found in the Old Testament (Ps. 141:2). Instead of burning bulls on an altar, the Church offers prayers as sacrifices. Churches are supposed to pray “on behalf of all men” (I Tim. 2:1), and also for civil rulers, that we might experience peace (I Tim. 2:2). The key phrase, of course, is “on behalf of” – the representative function.

Representation is inescapable. Van Til observes, “The covenant idea is nothing but the expression of the representative principle consistently applied to all reality.”[5] All of creation images God, especially man. And because of sin, man needs a representative to atone for him. Paul explains the representative principle when he says, “For if by the transgression of the one [Adam] the many died, much more did the grace of God and the gift by the grace of one Man, Jesus Christ, abound to many” (Rom. 5:15). Since mankind has no essential unity with God in His being, the human race always needs a representative before God. Christ is that representative.

We can summarize Biblical hierarchy as the idea that one represents others. Notice how individuals are chosen to represent larger groups in God’s Deuteronomic hierarchy (Deut. 1:9-18). In a sense, everyone is a representative and everyone needs a representative. No man stands alone. He has a representative either way; there is one at the top, like Moses; there is one at the bottom, like the captain over tens. Even the individual is in some sense representative of the whole group. If he sins, this affects the entire camp (Josh. 7). The idea of one for many cannot be avoided.

The Jews of Jesus’ day understood this principle. Caiaphas, the high priest that year, reminded the leaders of Israel that “it is expedient for you that one man should die for the people, and that the whole nation should not perish” (John 11:50). He was speaking of Israel’s political conflict with Rome. He understood that the representative principle operated here, as well as in other areas of life.

The representative hierarchy renders judgments (Deut. 1:9-18). We can even go so far as to say that it mediates the covenant. By rendering its decisions, the Bible is applied in a practical way to God’s people. Life is mediated to them through Judgment. We should understand, however, that this mediation takes place on two levels. There is mediation with a capital M, and there is lower case mediation that grows out of this. The first is redemption, “messianic”; it brings salvation. Moses and all the redemptive deliverers of the Bible (judges, prophets, priests, David, Solomon, etc.) mediated life to Israel with a capital M. The ultimate Mediator, however, is Jesus.

Yet in Deuteronomy, there are also lower case mediators who administrate the covenant. They serve a judicial purpose, and fall into two categories. In one sense, the whole body of believers, general mediators of the covenant, is a representative of God (Exod. 19:6). So everyone in the covenant community can go directly to Him. But God appoints special overseers, like the ones in Deuteronomy 1:9-18. They have a special anointing to render judgment.

This is how God manifests His transcendence. He has Mediators who bring the message of salvation, and they in turn have representatives, general and special, who rule under them. This creates God’s visible sovereignty on the earth, making submission or accountability extremely important.

Accountability

The representative principle makes everyone accountable to someone. Everyone is supposed to be checked and balanced by someone else. If the man at the top is not accountable to any institution, there is tyranny. If the man at the bottom is not accountable, there is anarchy. Rebellion disrupts the whole process of representation. If the Mediators act autonomously, everyone suffers. Adam sinned, and destroyed the whole human race.

If special mediators rebel, the whole covenant community suffers. King David once became angry with the people, and decided to chastise them by taking them into war (II Sam. 24). He numbered the people, which was always done before battle, but he did not offer a sacrifice. God became angry with him. David was given a choice of one of three punishments. His decision eventuated in the death of seventy thousand people (II Sam. 24:15). A man can be a great man of God, have great insights, but his attempted autonomy can make him a man of blood.

If the covenant community (general mediators) rebels against its anointed leaders, not only do they suffer, but the whole world suffers. Their ecclesiastical anarchy inhibits the spread of the kingdom. Immediately after the section on Israel’s court system, their first encounter with the Canaanites is recorded (Deut. 1:19ff.). Israel is brought to the Promised Land to enter and possess it. They “rebelled against the command [hierarchy] of the Lord” and would not go in (Deut. 1:26). The consequences were disastrous. They ended up wandering around in the wilderness for forty years. And even more important, Canaan was not brought under the Word of God. In other words, the “world” was not subdued because of their rebellion.

Accountability has consequences for everyone, especially the world. There is no visible sovereignty in the world until the representative principle is working properly inside the covenant community. It is clear from Deuteronomy that the covenant is the training ground of accountability for dominion in the world. Until God’s people learned to submit to their leaders, they were not allowed to exercise rule in Canaan. Before they could bring Canaan under the covenant, they had to be trained in several principles of accountability.

Principles of Accountability

- Rebellion forced God’s people into a wilderness experience. Disobedience always leads there.

- It is here that the servant of God encounters certain other enemies whom he cannot defeat without submission to the hierarchy. Actually, they are usually “lesser” enemies. Israel’s wilderness experience is a perfect example. Foreign powers were brought down on them. Until they repented (Deut. 1:41-46), the message was, “Paganism will dominate you when you rebel against the Lord’s system of judgment.” When Israel failed with the “big” enemy, Canaan, God withdrew them into a situation where they could practice before “smaller” enemies. The Lord riveted His point, as He often does in the Bible, through a series of instructive encounters. Some of the enemies God commanded Israel to pass by without conflict, as in the case of the “sons of Esau” (Deut. 2:8). Others God told them to fight and destroy, as in the case of the Amorites (Deut. 3:8). Why were they to fight some and not others? This leads us to point three.

- Rebellion destroys unity among the brethren. God always directed Israel away from their closest “brothers,” like the “sons of Esau” and the “Moabites” (Deut. 2:1-25). When Israel learned not to fight with the ones closest to them, they became more unified. And when they quit fighting among themselves, they were ready to fight the real enemies, the Amorites and even Canaan (Deut. 2:24).

- Marching comes before fighting. Israel wandered for thirty-eight years (Deut. 2:14). They had to learn to march in military order before they would be able to fight in harmony.[6] God drilled them for over three decades. When they showed enough accountability to walk in formation, they were ready to begin to fight. The people of God have to learn how to submit when they walk, before they will be able to run.

- Submission comes before privilege. After Israel absorbed the lessons of accountability, they were given a covenant grant. This was usually a grant given to a vassal who had demonstrated exceptional faithfulness. Israel’s grant was Canaan (Deut. 3:12).

- The ways of rebellion are removed slowly. God waited until the older, rebellious generation died (Deut. 1:35). This gave the younger generation an extended course in wilderness training. They had to submit to God and each other to survive. Individualists do not survive in the wilderness. Like Jesus in the wilderness, Israel was prepared for any challenge. If they could live in the wilderness, they could conquer in civilization.

- The lack of accountability leads to idolatry. Moses makes the connection we saw in the life of Saul. Autonomous leaders and people end up worshipping the wrong god. Moses indicates this possibility in his last words, “So watch yourselves carefully… lest you act corruptly and make a graven image” (Deut. 4:15-16). Rebellion is as the sin of witchcraft (I Sam. 15:22-23)!

These are the fundamental principles of accountability. In time and through history, the representative principle became a way of life.

Appeals Court or Bureaucracy?

In Chapter One, I stressed the point that God is transcendent and immanent. He controls everything, but He knows everything personally. He is different from man, yet He is present with man. I said that this leads to a fundamental difference between the Biblical covenant structure and Satan’s covenant structure.

Satan is not all-knowing, all-seeing, or all-anything. He is a creature. Thus, he is neither transcendent nor immanent in the way that God is. He has power, and he can move from place to place, but he cannot be everywhere at once.

This makes Satan highly dependent on his subordinates. His chain of command must get information to him from all over the globe. He must get information from his demonic subordinates, and he must exercise power through them. This limits him. Therefore, Satan’s hierarchy is top down, whereas God’s hierarchy is bottom up. God is in no way dependent on the creation, including His hierarchy, either angelic or human. Satan is dependent. So, in order to exercise his power, he must place great emphasis on his hierarchy. It is a classic bureaucracy. The being at the top exercises power through the chain of command as a military commander exercises power. It is a top-down chain of command.

The Church, like Christian institutions in general, is not structured along the lines of a top-down hierarchy. God knows all things, and He controls all things. Thus, He can safely delegate responsibility to subordinates, in a way that Satan dares not delegate power. Satan commands ethical rebels who threaten him; God commands everything, and no one can threaten Him. It is the very sovereignty of God that is the basis of the decentralized freedom of individuals in Christian society. It is the non-sovereignty of Satan that leads always to centralized power and bureaucracy. What Satan cannot achieve as a creature he attempts to achieve through centralized power and top-down bureaucracy.

This is the issue of omniscience. To exercise total authority the director needs perfect knowledge. In the Biblical social order, no institution needs such omniscience precisely because the Head, Jesus Christ, possesses it, and so does the Holy Spirit, who speaks to every covenantally faithful person. We have access to the Bible, and we have access to God in prayer. Thus, we can be left free to work out our salvation in fear and trembling (Phil. 2:12). Decentralization becomes possible in such a world.

Exodus 18 and Matthew 18

In Exodus 18, we have the story of Moses the judge. Every petty dispute is brought to him, for he has access to perfect judgment. God speaks to him. But the lines get too long. Justice is delayed. The people wear Moses out. So Jethro, his father-in-law, comes and tells him to allow the people to appoint righteous judges above them. The people need to get speedy justice, so they can get back to dominion. Better imperfect speedy justice in most cases than perfect justice after weeks or months of standing in line. Better dominion activities than standing in line.

What is the universal mark of all government bureaucracies? Standing in line. All over the Communist world, people stand in lines. They wait.

Moses set up an appeals court structure. Men were free to work out their salvation with fear and trembling. There was self-government under God. Only when there were disputes was the Biblical civil hierarchy invoked. This is even more true in New Testament times. Matthew 18:15-18 outlines the same sort of appeals court procedure for the Church – a hierarchy of bottom-up courts. The progression is from the private dispute to the public court of the church. Men need to get disputes settled properly, to reduce bickering and allow a return to the dominion activities of life. Things need to be settled if dominion is to proceed.

War

It is true that in wartime, civil governments adopt a top-down chain of command, but only for military personnel. To the extent that they try to run the economy by a bureaucratic system, production bottlenecks appear, and the economy becomes more irrational. The chain of command is supposed to be limited to warriors and battles.

We must recognize that military warfare is an exception to the normal activities of life. War is an extraordinary measure. In the Old Testament, the civil government numbered the people only before a military engagement. Each adult male twenty years old and older had to bring a heave offering of half a shekel of silver. This was a payment to make atonement (Ex. 30:12-16). When David numbered the people for the purpose of going to war, and he failed to make this atonement, God punished him by killing 70 thousand Israelites in a plague (II Sam. 24). He was acting like a pagan king, shedding blood without proper atonement.

It is true that we are in perpetual spiritual warfare in the New Covenant (Eph. 6). It is also true that they were in perpetual spiritual warfare in the old covenant. Spiritual warfare is ordinary; military warfare is extraordinary. This is why Christians are told to pray for civil peace (I Tim. 2:1-2). It is in peacetime that we can best do our work of dominion. A full-time military warfare State is an ungodly, satanic bureaucracy. In fact, war or the coming of war is used as the primary excuse to centralize the nation. Wars and rumors of wars are part of a fallen world, but we are not to indulge ourselves in perpetual war for perpetual peace.

The Biblical strategy for winning the spiritual war is self-government under God. Wars begin in the heart (James 4:1). The best means of keeping the peace is covenantal faithfulness (Deut. 28:1-14). Suppress the war of the heart, and the result is greater peace. The presence of the Biblical hierarchy helps men to face what is in their hearts. As we have already seen, Matthew’s chapter on discipline outlines a bottom-up hierarchy similar to Moses’ (Matt. 18:15ff.).

The priests of the Old Covenant did not operate a top-down bureaucracy. Why, then, should we, who have the Holy Spirit, seek to create a top-down bureaucratic hierarchy in any area of life except the military? We have the Bible – our marching orders – and we have prayer and therefore access to the throne room of God. There is no reason to imitate Satan’s hierarchy, as if our Commander-in-Chief were not omnipotent, omniscient, and omnipresent. We should instead limit earthly hierarchies to appeals courts under God.

Redemptive History

History is covenantal.[7] It is the story of the application of the covenant in God’s world. No covenant – no space, time, or history. The historical section of Deuteronomy is a miniature picture of this relationship between history and covenant. What happens in the second segment of Deuteronomy with God’s representatives happens on a larger scale throughout the Bible. Consider the following overview: a hierarchy (Deut. 1:9-18), a fall of the hierarchy (Deut. 1:19-46), a series of tests (Deut. 2:1-3:29), judgments (4:1-24), and finally the transition from Moses to the new leadership of Joshua, a superior hierarchy (Deut. 4:25-49). All of these parts track Biblical history. As we saw earlier, Adam and Eve were God’s hierarchy. Shortly after their creation, they fell. They faced a test and failed. Then God judged them and promised a new hierarchy in the form of a seed. This pattern repeats itself over and over again. We can say there is similarity. But, there is dissimilarity, as we see in the Bible that Adam’s seed does not have the power to bring in a new hierarchy. God must send His Son in a miraculous way. Nevertheless, God summarizes Biblical history in this short segment of Deuteronomy.

Thus, we can posit two principles about the redemptive history of the Bible by comparing it to Deuteronomy (1:9-4:49).

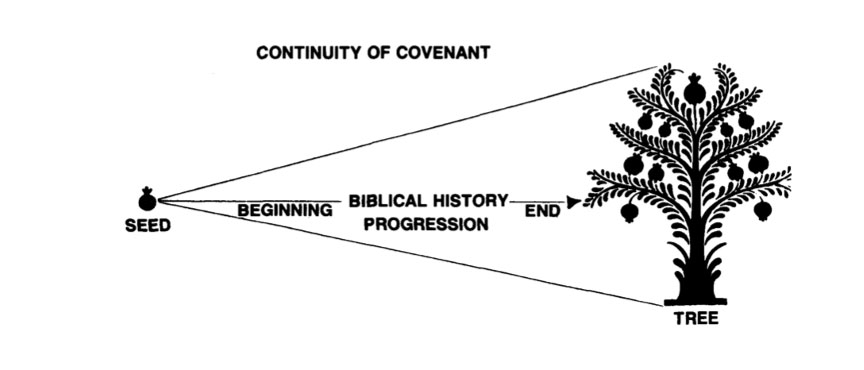

First, just as there is similarity between Deuteronomy and the New Covenant that Jesus established, we can derive a principle of similarity in redemptive history. The similarity is in the covenant because the covenantal structure is repeated. Just as everything about a human being is encoded in those first cells of his existence, so the first beginnings of the covenant in Genesis are encoded in seed form. The following diagram pictures the growth of the covenant like a seed, containing everything from its first inception that it will eventually become in a much fuller sense.

Second, just as there is dissimilarity in the progression from Moses to Joshua in Deuteronomy, there is a principle of dissimilarity in redemptive history because of its progress and development. God continues to reveal Who the true representative will be, and He brings about significant changes. So the representative principle helps us to understand history itself. When we come to the Bible, we should keep the similarity and dissimilarity concepts in mind. There will be the application of the covenant at every point, including a Mediator and mediators who follow Him. But there will also be progress as these representatives continue to fail.

Redemptive History, Old and New

The Bible describes a representative sacrificial and service system where some representatives are nearer to God than others. In Deuteronomy 1:9-18, Moses was at the top of the layers of representatives. In other words, there were degrees of closeness to God. James Jordan explains this elaborate hierarchy.

- The High Priest acted as priest to the house of Aaron, the Levites, Israel, and the nations.

- The house of Aaron, including preeminently the High Priest, acted as priests to the Levites, Israel, and the nations.

- The Levites, including the house of Aaron and the High Priest, acted as priests to Israel and the nations.

- Israel, including the Levites, the house of Aaron, and the High Priest, acted as priests to the other nations.[8]

All through the Old Covenant, we see that men stood between God and their fellow men. Progressively, however, there was movement to that one day when everything changed. This is implied in the shift from Moses to Jesus. When Jesus came, the principle of representation remained the same, but its application changed. Jordan explains this change.

With the coming of the New Covenant, these dualities were transformed. The New Covenant embodies the fulfillment of what the First [or Old] Covenant with Adam was supposed and designed to bring to pass, but never did…. There is no one Edenic earthly central sanctuary; rather, the sanctuary exists in heaven and wherever the sacramental Presence of Jesus Christ is manifest. The equivalent to being in the holy land is now to be in the Body of Christ.[9]

We still come to God by representation in Jesus Christ, but we have direct access to God. Through prayer, the Church has even greater access than the High Priest had in the Old Testament. He could only directly approach God once a year. We can come directly to God any time we want! The veil of the Temple was torn at Christ’s death. The separation between the Holy of Holies and the sanctuary was removed.

The Old Testament believer could pray, but His prayer life was more restricted. The Holy Spirit has come in the New Testament, and He intercedes in a special way. ”And in the same way the Spirit also helps our weakness; for we do not know how to pray as we should, but the Spirit Himself intercedes for us with groanings too deep for words; and He who searches the hearts knows what the mind of the Spirit is, because He intercedes for the saints according to the will of God” (Rom. 8:26-27). With the substitution of Jesus as the High Priest of God, who now sits at the right hand of God, the New Testament believer has a full-time intercessor or intermediary or representative in the throne room of God. The Spirit also can now intercede for us in a special way. The incarnation, death, resurrection, and ascension of Christ in history have made a fundamental difference in heaven.[10]

The effect of this shift in representation has brought about a direct-access view of government. The genius of Biblical representational government is that everyone in the Church has access to the “Man at the top.” This leads to progress. There is less bureaucracy. In the Old Covenant, there was one man once a year who could approach God. Now there are thousands of men and women of every nationality and every race approaching God every moment of the day, twenty-four hours a day, every day of the year. This kind of communication from the bottom up creates greater activity, interest, and progress. God wants it this way because He designed the system!

Furthermore, the hierarchy and history of Deuteronomy 1:6-4:49 implies a transformational progression of history. Joshua implemented Moses’ covenant. The ingredients of the covenant under Moses remained the same. The application was worked out through a new Head of the covenant. The change was not radical but transformational. In other words, the Old Covenant was not radically abolished; rather, it came under a new regime in history because of the incarnation, death, resurrection, and ascension of Christ. This seems to establish the proper sense in which the Old Covenant shifted to the New Covenant. Harvard legal historian Harold J. Berman states the change:

In contrast to the other Indo-European peoples, including the Greeks, who believed that time moved in ever recurring cycles, the Hebrew people conceived of time as continuous, irreversible, and historical, leading to ultimate redemption at the end. They also believed, however, that time has periods within it. It is not cyclical but may be interrupted or accelerated. It develops. The Old Testament is a story not merely of change but of development, of growth, of movement toward the messianic age-very uneven [covenantal] movement, to be sure, with much backsliding [covenant unfaithfulness] but nevertheless a movement toward. Christianity, however, added an important element to the Judaic concept of time: that of transformation of the old into the new. The Hebrew Bible became the Old Testament, its meaning transformed by its fulfillment in the New Testament. In the story of the Resurrection, death was transformed into a new beginning. The times were not only accelerated but regenerated. This introduced a new structure of history, in which there was a fundamental transformation of one age into another.[11]

The effect of this transformational view of hierarchy means representation and accountability are still part of God’s covenantal program. These ideas pull through to the Church. Granted, Christ is head of the covenant, and there is not the kind of elaborate hierarchy as is in the Old Testament. All men have access to God. Christ is the Mediator, capital M. But God still establishes representatives, elders (bishops and pastors), who pass judgment. They mediate with a small m. Thus, we can observe the same principles in the Church that we saw operative in Israel. Church members should obey Christ and His Word as well as its representatives as they attempt to apply the Bible.

Notice that the Book of Acts contains such an example. In the early Church, Ananias and Sapphira lied to the Holy Spirit, as He was represented by the Apostolic authority (Acts 5:1-7). The Spirit struck them dead. Even so, the following passages reveal that great persecution came on the Church (Acts 5:17-42). The implication is that the same thing happened to the Church that happened to Israel. When the Church rebelled, the enemies of the Church took them into captivity.

So there was change with the coming of the New Covenant, but the change was transformational, not radical. The change was total but not total obliteration of the covenant. The covenant shifted from Old to New.

Conclusion

God’s hierarchy is established in history. A denial of Biblical authority and hierarchy is ultimately a denial of history. A rejection of history eventually gives up God’s hierarchy. When Associate Professor of Bible and Religion at Emory University, Atlanta, Georgia, Thomas J. Altizer, wanted to reject the God of the Bible, he said, “God has died in our time, our history, our existence.”[12]

The second principle of the covenant is the historical prologue, called the hierarchical principle. What have I attempted to do in this chapter? First, I presented the relationship between hierarchy and the first point of covenantalism. I said that hierarchy is the manifestation of God’s transcendence. Hierarchy is visible sovereignty.

Second, I talked about the representative principle. God begins the historical section of Deuteronomy with a description of the court system in Israel. Everyone had a representative, and everyone was accountable. In this context, we saw seven principles of accountability.

Finally, I examined the relationship between hierarchy and history. In general, the historical section of Deuteronomy is a miniature picture of the whole redemptive process of Scripture. So there is similarity through all the parts of the Bible. They all grow out of a basic covenantal structure established in Genesis. Yet, there are dissimilarities due to the progression of revelation.

Next in the Biblical covenant we come to the principle of ethics. The heart of man~ bond to God is the fulfillment of righteousness. In this section I will make the most important statement of the book. I will present the concept that there is an ethical relationship between cause and effect.

[1] Kline, Structure of Biblical Authority, pp. 114-115. Kline refers to the treaty of Mursilis and his vassal Duppi-Teshub of Amurru. He says, “Such treaties continued in an ‘I-thou’ style with an historical prologue surveying the great kings previous relations with, and especially his benefactions to, the vassal king.” A translation of this treaty, along with many others, can be found in A. Goetze, Ancient Near Eastern Texts, ed. J. B. Pritchard (Princeton: Princeton University Press, 1950), pp. 203ff.

[2] Sometimes written vice regent.

[3] This does not mean that the institutional Church is to control politics (ecclesiocracy). It means that Biblical principles are to govern the affairs of men.

[4] James B. Jordan, The Law of the Covenant: An Exposition of Exodus 21-23 (Tyler, Texas: Institute for Christian Economics, 1984), p. 190.

[5] 5. Cornelius Van Til, Survey of Christian Epistemology (Grand Rapids: Den Dulk Christian Foundation, 1969), Vol. II, p. 96. Emphasis added.

[6] James B. Jordan, The Sociology of the Church: Essays in Reconstruction (Tyler, Texas: Geneva Ministries, 1986), pp. 215-16.

[7] R. G. Collingwood, The Idea of History (Oxford: Clarendon Press, 1946), p. 52. Collingwood said, “Any history written on Christian principles will be of necessity universal [transcendent], providential [hierarchical], apocalyptic [sanctions], and periodized [continuity].” I have added brackets to show how Collingwood’s assessment of Christian interpretation of history easily fits the covenantal scheme I am presenting in this book. Gordon H. Clark, Historiography: Secular and Religious (Nutley, New Jersey: Craig Press, 1971), pp. 244-245, even refers to Collingwood’s four points and adds a fifth: “revelation.” This would fit the third point of covenantalism called “ethics,” or law, being “special revelation” to man.

[8] James B. Jordan, Sabbath Breaking and the Death Penalty (Tyler, Texas: Geneva Ministries, 1986), p. 32.

[9] Ibid., p. 17.

[10] The Spirit takes the place of the cherubim. The mercy seat is Christ.

[11] Berman, Law and Revolution, pp. 26-27. Emphasis added. On Berman’s observation about a “linear” view of time, it should be remembered that Augustine’s City of God was a defense of a Christian interpretation of history. When the barbarians sacked Rome, some argued that Rome had been “cursed” because of the spread of Christianity and a betrayal of the “old” gods. Augustine countered by defending the idea of a “city of God,” at war with the “city of the earth,” which in my opinion was not to disregard completely the notion that Rome was “cursed” for its failure to embrace fully the Christian religion. For an interesting discussion of Augustine’s linear view of time, as opposed to Basil’s more cyclical interpretation, see Jean Danielou, The Bible and the Liturgy (Ann Arbor: Servant Books, [1956] 1979), pp. 262-286.

[12] Thomas J. Altizer, Mircea Eliade and the Dialectic of the Sacred (Philadelphia: Westminster Press, 1963), p. 13.